Chips Off the Old Block

and other ruminations about masonry

by

by

Manufactured Stone Veneer

Some of you probably recall the early days of exterior insulation and finishing systems (EIFS). EIFS was first used in North America in the 1960s, and became very popular in the mid-1970s. I worked with Richard (Dick) Crowther in those days, a pioneer in energy-conscious and energy-conserving architectural design, predating the work of the USGBC by some 20 years. One of the design idioms that became the hallmark of Crowtherian designs was the idea of exterior insulation. Dick was a vocal proponent of exterior insulation because it mitigated the thermal bridging that was common in buildings that featured only batt insulation between the wall studs.I had the opportunity to work on many leading-edge energy conserving designs, most of which were residential. But I worked on one very special commercial building -- the national headquarters for The Hotsy Corporation.

|

| The Hotsy Corporation National Headquarters |

This building, built in 1977, was loaded with energy-conserving features and many opportunities for interior daylighting. And it was designed using state-of-the-art EIFS materials and details. However, the state-of-the-art for EIFS in 1977 was, unfortunately, not very advanced. These early EIFS systems trapped water that leaked in around doors and windows. The moisture damage that was concealed behind EIFS cladding systems was first discovered in this country in 1995, in Wilmington, North Carolina.

[Buildings] clad with EIFS ... have a very strong tendency to retain moisture between the sheathing of the home and the finish system. The design of EIFS, unlike other systems (brick, stone, siding, etc.), does not allow the moisture to drain out. The problem is water intrusion and entrapment in the wall cavities. The moisture can sit in contact with the sheathing for a prolonged period and rotting may result. Damage can be serious.

While a brick or stone wall will contain an internal drainage plane behind it and weep holes along the bottom edge to allow for water drainage, moisture intruding into the EIFS wall cavities is more damaging because it cannot readily escape back out through the waterproof EIFS exterior as quickly as it can through brick veneer, stone, or cement stucco, leaving the internal sheathing and wood framing vulnerable to rot and decay. (EIFS Facts, Douglas Pencille)

The solutions to this problem were many-fold, but foremost among them was a philosophical change from the belief that EIFS could be a successful “barrier” or "face-sealed" system to the realization that it really needed to be a “drainage” system. Now the EIFS state-of-the-art mandates that drainage methodologies be used, except in limited (mostly hot and dry) locations.

Why am I discussing EIFS in an article about manufactured stone veneer? The reason is simple. MSV (Manufactured Stone Veneer is called by many names in the industry, but probably a more appropriate term would be Adhered Manufactured Stone Masonry Veneer [AMSMV], although the issues pertain to the use of real stone veneer as well) is following a path that is very similar to the path followed by the EIFS industry. And very interestingly, the state of North Carolina seems to be taking the lead in addressing the issues thru its inspection system. But I am certain that jurisdictions in Colorado are right there beside them.

|

| Manufactured Stone Veneer |

|

| MSV units |

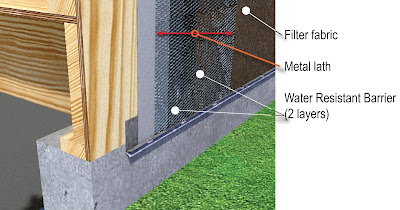

Masonry veneer systems have been developed and refined for many years, and some of the recommendations we take for granted today came about as responses to problems that were discovered in the early years. One of those “recommendations” (I use the term “recommendations” with caution because if you were to fail to adhere to the "recommendations" and a problem were to develop, you would be very far out on a very thin branch with no help in sight) is the use of an air space behind the brick veneer, and then a drainage plane covering the water-sensitive materials. MSV systems are commonly installed with no air space. Metal lath (or sometimes in residential construction, a woven-wire lath also known as chicken wire) is stapled thru a building paper or asphaltic building felt (this is the Water Resistive Barrier --WRB) Then the mortar scratch coat is applied to the metal lath to hold the veneer stones. It is is applied in contact with that WRB. When it rains, the system becomes saturated, and water migrates towards the WRB via suction. But since there is no air space to enable drainage, the water is held against the paper drainage plane. In a masonry system, the weather resistive barrier may get wet, but the air space allows the system to both drain along the drainage plane, as well as access to air to help dry it out. In an MSV system, once it gets to the WRB, to paraphrase Richard Gere in An Officer and a Gentleman, it‘s "got nowhere else to go." Eventually, the current thinking is that it will be absorbed by the mortar and concrete materials, from which it can evaporate, or it will make its way down to the weep screed, where it should be able to exit the system.

In the next installment, I’ll talk more about what is required to make the MSV system more effective at resisting water intrusion. In the meantime, I believe you my find it interesting to review the Masonry Veneer Manufacturers' Association (MVMA) testing to determine the effectiveness of MVS systems in preventing water intrusion. The following tests were conducted by Architectural Testing, Inc. on a veneer system without a rainscreen (a path for water to escape and air to enter) and also with a rainscreen. The tests were conducted according to the protocols in ASTM Standard E331. Neither system suffered any failures.

In a publication entitled Adhered Natural Stone Veneer Installation Guide (see below) authored jointly by the Rocky Mountain Masonry Institute, Atkinson-Noland Engineers, and Robinson Brick Company, the issue of using rain screens is not addressed in detail. The publication says only that the use of rainscreens is optional. However, a number of authorities having jurisdiction around the country require the use of rainscreens in manufactured stone veneer systems.

Masonry Veneer Manufacturers' Association

Water Penetration Test -- No Rainscreen

Water Penetration Test -- With Rainscreen

Masonry Veneer Installation Guide

NOTE: This document was prepared by the JNX Group, LLC and is disseminated for informational purposes only. Nothing contained herein is intended to revoke or change the requirements or specifications of individual manufacturers or local, state and federal building officials that have jurisdiction in your area. Any question, or inquiry, as to the requirements or specifications of a manufacturer, should be directed to the manufacturer concerned. The user is responsible for for assuring compliance with all applicable laws and regulations.

The information provided here is provided for informational purposes only, and includes the opinions of the author. Nothing contained herein shall be interpreted as an endorsement of any particular product or manufacturer, or as a warranty by JNX Group, LLC, either express or implied, including but not limited to the implied warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose or non-infringement. In no event shall JNX Group, LLC be responsible for any damages whatsoever, including special, indirect, consequential or incidental damages or damages for loss of profits, revenue, use or data, whether claimed in contract, tort or otherwise.